In my previous article Unconscious Decision Making, I sang the praises of unconscious intuition in regards to its superior ability in complex decision making. A couple of months ago in a two-part article Should You Trust Your Intuition?, I described areas where intuition both works well and areas where it doesn’t work so well. Two of those not so well areas were risk and probability. Our intuition about risk stinks.

Irrational and unfounded fears have long been topics of interest to me. I like to dig deeper into the numbers and probabilities. My Amazon recommendations have included a book called The Science of Fear: Why We Fear the Things We Shouldn’t–and Put Ourselves in Greater Danger by Daniel Gardner for what seems like a year. I recently noticed the $25 hardcover was bargained priced for under $7 so I bought it.

I absolutely loved this book. It is crammed full of meaningful numbers, statistics, and probabilities. Virtually every page and sometimes every paragraph references research, experiments, or actual numbers relevant to the topic being discussed. It is a treasure trove of data about risk and for that reason alone is very valuable. But that’s not the best thing about this book. I’ve encountered similar data before, albeit not all in one place. What I really liked about this book is that the author does an outstanding job of explaining the evolutionary psychology and sources of our fears. He has a number of fairly in-depth chapters that dissect various areas of risk like health, crime, and terrorism. This isn’t a dry book of numbers, instead it is a very well written and researched explanation of why we fear things that we shouldn’t. I highly recommend it.

In Part I, I will describe some of the reasons why we make so many mistakes in our intuitive calculations of risk and thus fear things that we shouldn’t or ignore risks to which we should pay attention. In The Science of Fear – Part II, I will provide some of the numbers and probabilities that I find relevant to current events.

The Emotion of Fear

Fear is an important emotion that had extremely important survival value in the world in which our brains developed. Much of that value is now being misdirected. The emotional makeup of fear is now a big part of what leads to our miscalculation of risk. Further, those with economic or political value to be gained, use the emotion of fear to influence us. It’s easy to motivate people by scaring them. So to truly understand and react to risk in a reasonable manner, we must approach it in a cold and calculating way.

This might lead some to think the certain unlikely events are being treated dismissively or unsympathetically. This is not the case. The fact that extremely unlikely events happen to people is undisputed. If something awful has happened to you or to someone you love, and this article describes something similar as “unlikely”, please don’t take it personally. You have my deepest sympathy.

Even something that only happens to one in one million people every year is going to generate an average of one case per day in the United States. The fact that unlikely events happen to someone does not mean they are any more likely to happen to you or me. A lady once won two different mega-million dollar lotteries. The odds against it were calculated to be one in seventeen billion (three times the population of the world). The fact it happened to someone somewhere, does not mean I should change my behavior on the assumption it could happen to me. That would be foolish. We all have a precious limited number of minutes on this earth and I for one don’t intend to waste them on misperceived dangers.

Two Minds

Gardner talks a lot about the gut (unconscious) and the head (conscious) and the battle between the two over fear. Unfortunately most people are ignorant of the numbers and the head is doomed to lose from that fact alone. However, even when the head knows the numbers, it often does not overrule the gut. The rules of thumb used by our brains are just too hardwired to completely overcome. The best it can do is modify the decision of the gut, but it will still not modify to nearly the degree that logic would indicate. Further, if the gut is reacting to something particularly emotionally compelling, the head will have almost no influence. Regardless, the only hope we have is to understand the probabilities and do our best to act in accordance with the actual risk. We need to become good with numbers.

The Example Rule

Our caveman brains developed in a world in which we knew very little about anything that was not directly experienced by us or our small band of local hunter-gatherers. So our brains developed a useful, but not perfect, rule of thumb. The more easily something was able to be recalled the more likely it was to occur.

One scary emotional experience, such as being chased by a lion which leaped out of the tall grass, would be seared into our brain and would be instantly recalled when we were in a similar situation. We would be afraid there might be lions lying hidden in the grass and rightfully so. Seeing someone in our tribe being chased by a lion would also be easily recalled, if not quite to the same degree as being chased oneself. Finally, we learned of many dangers by listening to the stories others in our tribe told. The more frequently we heard similar stories, the more easily they were recalled.

In this manner the most common and/or most dangerous local experiences were the most easily recalled and considered most likely. It was a good rule of thumb. But imagine if cavemen in a cave in Europe were there were no lions, watched daily television news (just go with me on this) of lions leaping out of grass and devouring people on African savannah? These dramatic experiences might make them so afraid of strange monsters hiding in the grass, that they would be afraid to venture into their own grasslands and hunt the food they needed to stay alive.

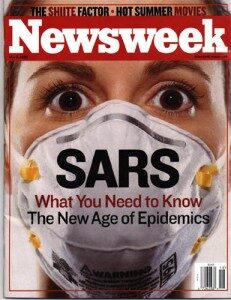

Brains that developed rules of thumb that worked well when we were geographically and socially isolated to our own local environments, must now deal with information they get from living in an electronic tribe of six billion members. An extremely rare risk of say 1 in 1,000,000 per annum is going to happen every single day on average in a population of 350,000,000 in the U.S.

If the TV or internet video blasts nonstop dramatic pictures of those events into our brains, those brains are going to be fooled into thinking something of virtually no risk is actually a high risk. When extremely unlikely shark attacks are the subject of almost daily reporting in the media, our caveman brains assume that sharks attacks are a common danger. Studies that question people on the probability of dangerous events show exactly that; they think unlikely events are actually likely. Since the head can’t completely overrule the gut, even when we are aware the risk is not that great, we can’t get rid of the fear and we will behave irrationally. We may actually stay out of the water or just not enjoy the experience because instead of relaxing, we are on the lookout for sharks.

The Typical Rule

We are pattern seeking animals. We hold in our minds patterns of things that we believe typically go together. This enables us to make snap judgments that are often right or contain some degree correspondence to reality. But they can also be completely wrong.

We like to tell stories. Stories are a basic part of our social environment. When we hear a story with what we believe to be typical components strung together into a compelling narrative, we tend to believe it likely to happen. Experiments have shown that creating a narrative of combined events that logically is much more unlikely than any of the components individually, may be considered more likely by the subjects of the experiment. This is exactly opposite of the actual probabilities.

So when marketers want to sell us lockdown security for our homes or the government wants to take away our liberty or privacy in the name of “homeland security”, they will weave plausible sounding and compelling narratives that are extremely unlikely. Our brains react exactly the same as in the experiments. We buy it. This is also why we can be in continual fear of expert predictions of future doom scenarios. Historically these predictions turn out less accurate than monkeys throwing darts.

The Good-Bad Rule

What feels good must be good. While that works much of the time, sometimes it does not. Smoking a cigarette makes a smoker feel better so it must not be that bad for him. Sugar tastes good and that means I should eat more of it. Experiments have shown that experiences that are associated with positive emotions are considered less dangerous than those associated with negative emotions, regardless of the real risks.

The Familiarity Rule

You tend to like what is familiar. The more times you hear a song (within reason) the more you like it. The more familiar you are with something, the better it makes you feel and the less dangerous it seems. The less familiar you are with something, the more dangerous it seems. I guess this is why sitting on a couch drinking beer and eating pizza every night doesn’t seem particularly dangerous, while at the same time a vision of an airplane flying into a tall building makes you afraid of terrorists The lifestyle danger is almost guaranteed to harm you and the terrorist danger is essentially non-existent.

Mothers will not let their children walk to McDonalds because they are worried about extremely unlikely stranger danger, but they seem to have no problem feeding them killer French fries once they have “safely” driven them to the restaurant. Europeans will march in a protest against genetically engineered foods that hundreds of millions of Americans eat every day without so much as a case of indigestion, and then go sit in a cafe and smoke a cigarette and talk about the poisonous American food.

The Herd Rule

This one is very simple. We fear things that others fear. We are influenced by and to some degree follow the herd. This makes sense. If the rest of the hunting party believed there were lions in the grass, it would be wise to follow their lead. This doesn’t work out so good when other people are afraid of terrorists or stay inside because of West Nile Virus.

Our brains no longer judge risk accurately in this strange world we have created for ourselves. Therefore, it is important that each one of us carefully examines actual real-world risk and then acts accordingly.

To be continued in The Science of Fear – Part II

What do you think? Leave a comment and join the conversation.

Tagged as: fear, probability, Psychology, risk